2型糖尿病:修订间差异

撤销36.225.98.36(讨论)的版本40051075 |

|||

| 第75行: | 第75行: | ||

===药物=== |

===药物=== |

||

[[File:Metformin 500mg Tablets.jpg|thumb|[[二甲双胍]]500mg片剂]] |

[[File:Metformin 500mg Tablets.jpg|thumb|[[二甲双胍]]500mg片剂]] |

||

目前有几类[[抗糖尿病药]]。由于有证据表明[[二甲双胍]]({{lang|en|Metformin}})可降低死亡率,因此通常将其作为第一线治疗药物。<ref name="AFP09"/>如二甲双胍不足以控制病情,则可使用另一个类的辅助口服制剂。<ref>{{cite journal|last=Qaseem|first=A|coauthors=Humphrey, LL, Sweet, DE, Starkey, M, Shekelle, P, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of, Physicians|title=Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians|journal=Annals of internal medicine|date=2012-02-07|volume=156|issue=3|pages=218–31|pmid=22312141|doi=10.1059/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00011}}</ref>其他类别的药物包括:[[磺酰脲类]]、[[抗糖尿病药#非硫醯基尿素類|非磺脲类分泌抑制剂]]、[[α-葡萄糖苷酶抑制剂]]({{lang|en|alpha-glucosidase inhibitor}})、[[噻唑烷二酮类药物]]({{lang|en|Thiazolidinedione}})、[[胰高血糖素样肽-1类似物]] |

目前有几类[[抗糖尿病药]]。由于有证据表明[[二甲双胍]]({{lang|en|Metformin}})可降低死亡率,因此通常将其作为第一线治疗药物。<ref name="AFP09"/>如二甲双胍不足以控制病情,则可使用另一个类的辅助口服制剂。<ref>{{cite journal|last=Qaseem|first=A|coauthors=Humphrey, LL, Sweet, DE, Starkey, M, Shekelle, P, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of, Physicians|title=Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians|journal=Annals of internal medicine|date=2012-02-07|volume=156|issue=3|pages=218–31|pmid=22312141|doi=10.1059/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00011}}</ref>其他类别的药物包括:[[磺酰脲类]]、[[抗糖尿病药#非硫醯基尿素類|非磺脲类分泌抑制剂]]、[[α-葡萄糖苷酶抑制剂]]({{lang|en|alpha-glucosidase inhibitor}})、[[噻唑烷二酮类药物]]({{lang|en|Thiazolidinedione}})、[[胰高血糖素样肽-1类似物]]、[[二肽基肽酶-4抑制剂]]({{lang|en|Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor}})以及[[钠-葡萄糖协同转运蛋白2抑制剂]](SGLT2抑制剂)。<ref name="AFP09"/><ref>{{cite journal |author= |title=Standards of medical care in diabetes--2012 |journal=Diabetes Care |volume=35 Suppl 1 |issue= |pages=S11–63 |pmid=22187469 |doi=10.2337/dc12-s011|last1= American Diabetes |first1= Association|date=January 2012}}</ref>二甲双胍不应该用于患有严重肾脏或肝脏功能异常的患者。<ref name="Vij2010"/>[[胰岛素]]注射可用于配合口服药物治疗,或单独使用。<ref name="AFP09"/> |

||

大多数人最初都无需注射[[胰岛素]]。<ref name="Green2011"/>当使用时,通常在夜间采用一种长效制剂,同时继续口服药物。<ref name="Vij2010"/><ref name="AFP09"></ref>剂量随后增加至起效(血糖水平达到很好的控制)。<ref name="AFP09"/>当夜间胰岛素不足,每日两次胰岛素可达到更好的控制。<ref name="Vij2010"/>长效胰岛素,[[甘精胰岛素]]({{lang|en|glargine}})和[[地特胰岛素]]同样安全、有效,<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Swinnen | first1 = SG. | last2 = Simon | first2 = AC. | last3 = Holleman | first3 = F. | last4 = Hoekstra | first4 = JB. | last5 = Devries | first5 = JH. | title = Insulin detemir versus insulin glargine for type 2 diabetes mellitus | journal = Cochrane Database Syst Rev | volume = | issue = 7 | pages = CD006383|year = 2011 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD006383.pub2 | pmid = 21735405 | editor1-last = Simon | editor1-first = Airin CR}}</ref>并不比中性[[NPH胰岛素]]更好,但因为花费明显更高,所以它们不具备成本效益。<ref>{{cite journal|last=Waugh|first=N|coauthors=Cummins, E, Royle, P, Clar, C, Marien, M, Richter, B, Philip, S|title=Newer agents for blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and economic evaluation|journal=Health technology assessment (Winchester, England)|date=2010 Jul|volume=14|issue=36|pages=1–248|pmid=20646668|doi=10.3310/hta14360}}</ref><ref group="注">截至2010年不具备成本效益</ref>对于怀孕的患者,胰岛素是通常的治疗选择。<ref name="Vij2010"/> |

大多数人最初都无需注射[[胰岛素]]。<ref name="Green2011"/>当使用时,通常在夜间采用一种长效制剂,同时继续口服药物。<ref name="Vij2010"/><ref name="AFP09"></ref>剂量随后增加至起效(血糖水平达到很好的控制)。<ref name="AFP09"/>当夜间胰岛素不足,每日两次胰岛素可达到更好的控制。<ref name="Vij2010"/>长效胰岛素,[[甘精胰岛素]]({{lang|en|glargine}})和[[地特胰岛素]]同样安全、有效,<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Swinnen | first1 = SG. | last2 = Simon | first2 = AC. | last3 = Holleman | first3 = F. | last4 = Hoekstra | first4 = JB. | last5 = Devries | first5 = JH. | title = Insulin detemir versus insulin glargine for type 2 diabetes mellitus | journal = Cochrane Database Syst Rev | volume = | issue = 7 | pages = CD006383|year = 2011 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD006383.pub2 | pmid = 21735405 | editor1-last = Simon | editor1-first = Airin CR}}</ref>并不比中性[[NPH胰岛素]]更好,但因为花费明显更高,所以它们不具备成本效益。<ref>{{cite journal|last=Waugh|first=N|coauthors=Cummins, E, Royle, P, Clar, C, Marien, M, Richter, B, Philip, S|title=Newer agents for blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and economic evaluation|journal=Health technology assessment (Winchester, England)|date=2010 Jul|volume=14|issue=36|pages=1–248|pmid=20646668|doi=10.3310/hta14360}}</ref><ref group="注">截至2010年不具备成本效益</ref>对于怀孕的患者,胰岛素是通常的治疗选择。<ref name="Vij2010"/> |

||

2016年6月15日 (三) 14:35的版本

2型糖尿病(英語:Diabetes mellitus type 2,简称T2DM),旧称非胰岛素依赖型糖尿病(英語:noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus,简称NIDDM)或成人发病型糖尿病(adult-onset diabetes),是一种代谢性疾病。特征为高血糖,主要由胰岛素抵抗及胰岛素相对缺乏引起。[2]1型糖尿病与其为之不同的是,1型糖尿病患者身体因为胰脏里的胰岛细胞已经损坏,所以完全丧失了生产胰岛素的功能,使得他們必須依賴外在的補充劑來生存。[3]而2型糖尿病的典型病征为多尿症、多饮症(Polydipsia)以及多食症(Polyphagia)。2型糖尿病患者占糖尿病患者中的90%左右,其余10%主要为1型糖尿病与妊娠期糖尿病,因此後者可能被誤診。因遗传因素而易患糖尿病的高危人群中,一般认为引发2型糖尿病的主要原因是肥胖症。

2型糖尿病的早期是通过增加运动以及改变饮食习惯来控制病况的。如果这些办法无法把血糖降低至适当水平,可能要用到二甲双胍(Metformin)或胰岛素之类的药物。使用胰岛素的患者一般需要定期检查血糖水平。

自1960年以来,糖尿病与肥胖症的发病率同时出现了显著的上升,糖尿病患者从1985年的约3000万名剧增至2010年的约2亿8500万名。高血糖可引起慢性并发症,包括心血管疾病、中风、影响视力的糖尿病视网膜病变、可能需要采用透析治疗的腎衰竭以及可引致截肢的下肢血流不畅。酮症酸中毒为糖尿病急性并发症,一般常见于1型糖尿病病患者,在2型糖尿病患中属于罕见现象。[4] 然而,高渗性高血糖状态(Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state)也是可能会出现的并发症。

病征与症状

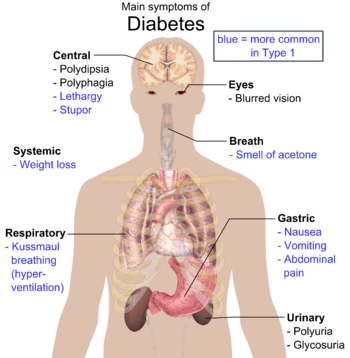

糖尿病的典型症状为多尿症、多饮症(Polydipsia)、多食症(Polyphagia)以及体重减轻。[5]诊断时其他常见的症状包括:视力模糊、皮肤瘙痒、周围神经病变(Peripheral neuropathy)、反复阴道炎、疲劳等病史。[3]然而,很多人在最初数年间不会出现病征,一般在常规体检中才被诊断出来。[3]患有2型糖尿病的人或会罕见地出现高渗性高血糖状态(Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state),一种高血糖伴有意识水平(level of consciousness)下降及低血压的病况。[3]

并发症

2型糖尿病是典型的慢性疾病,病发后的预期寿命较之病发前可减少10年。[6]导致预期寿命减少的部分原因是相关的并发症,包括:患上心血管疾病的风险是健康人群的二至四倍,其中包括缺血性心脏病、中风;下肢截肢率增加20倍,住院率亦相对增高。[6]在发达国家及越来越多的其他地区里,2型糖尿病是导致非创伤性失明及肾衰竭的首要原因。[7]在发病过程中,患者患上认知功能障碍(cognitive dysfunction)及失智症风险也会增高,如阿兹海默病及血管性痴呆。[8]其他并发症包括:黑棘皮症、性功能障碍,以及容易发生感染。[5]

病因

2型糖尿病的发病是因相关的生活方式与各种遗传因素相结合所引致的。[7][9]饮食习惯肥胖症等发病因素是人为可控制的,但其他容易导致发病的因素,例如年纪增长、性别为女性、遗传等其他因素则无法控制。[6]睡眠不足也与2型糖尿病有一定的关联。[10]有研究发现,睡眠不足会使致身体的新陈代谢有所改变,因而诱发2型糖尿病。[10]孕妇在胎儿发育过程中的营养状况也可能是一个发病原因,而当中DNA甲基化出现的改变是发病机制之一。[11]

生活方式

有不少生活方式方面的因素都被认为是引致2型糖尿病的重要因素,其中包括肥胖症和超重(指身高体重指数高于25)、体力活动不足、饮食习惯不健康、压力大以及生活城市化。[6]30%中国和日本血统的病患个案与体内脂肪过多有关,欧洲和非洲血统的有60%至80%,皮马印第安人和太平洋岛民的占了100%。[3]非肥胖症患者通常腰臀比过高。[3]

饮食也是影响2型糖尿病发病风险的重要因素。饮用过量的含糖饮料可增加患病风险。[12][13]饮食里摄取的脂肪类型也是很重要的因素:饱和脂肪与反式脂肪均增加患病风险,而多元不饱和脂肪与单元不饱和脂肪都有助降低风险。[9]进食大量白米似乎也会使致风险增加。[14]而有人相信,7%的病例与缺乏运动有关。[15]

遗传因素

大多数糖尿病个案与很多不同的基因有关,而这些不同的基因都可能会导致患上2型糖尿病的几率上升。[6] 如果一对同卵双胞胎其中一人有糖尿病,另一人患上糖尿病的机会可高于90%,然而非同卵的兄弟姐妹的几率是25%至50%。[3]到2011年为止,共发现了超过36个基因可增加患上2型糖尿病的风险。[16]然而,即使全部这些基因加在一起,亦只占诱发糖尿病的整体遗传因素中的10%。[16]例如,可使发病风险增加1.5倍的等位基因TCF7L2为常见的基因变异中引致最高风险的基因。[3]大多数与糖尿病有关联的基因都与β细胞功能有关。[3]

在一部分罕见的糖尿病个案中,发病原因是因单个基因出现异常而引起的(称为单基因型糖尿病或“其他特殊类型糖尿病”)。[3][6]其中包括年轻的成年发病型糖尿病(Maturity onset diabetes of the young,简称MODY)、矮妖精貌综合征(Leprechaunism)、Rabson-Mendenhall综合征等等。[6]年轻的成年发病型糖尿病占年轻糖尿病患者个案总和的1%至5%。[17]

健康状况

一部分药物和其他健康问题都会使人易患糖尿病。[18]部分药物包括:糖皮质激素、噻嗪类利尿剂(Thiazide)、β受体阻滞剂(β-blockers)、非典型抗精神病药物(Atypical antipsychotic)[19]及他汀类药物。[20]曾患妊娠糖尿病的人士患上2型糖尿病的风险相对较高。[5]其他相关的健康问题包括:肢端肥大症、皮质醇增多症、甲状腺功能亢进症、嗜铬细胞瘤(Pheochromocytoma)及某些癌症如胰高血糖素瘤(Glucagonoma)。[18]另外,睾酮缺乏与2型糖尿病也有很密切的关联。[21][22]

病理生理学

从病理生理学的角度来说,引起2型糖尿病的原因是,在出现胰岛素抵抗的情况下,β细胞无法制造足够的胰岛素。[3]胰岛素抵抗,即细胞无法对正常水平的胰岛素作出适当反应的现象,主要出现在肌肉、肝脏及脂肪组织。[23]在肝脏里,在正常的情况下,胰岛素会抑制葡萄糖的释出。但是,出现胰岛素抵抗时,肝脏会不适当地把葡萄糖释放到血液中去。[6]每个患者的胰岛素抵抗和β细胞功能障碍的比率都有所不同,其中一部分的情况或以胰岛素抵抗为主、轻微的胰岛素分泌缺陷为次,而其他的或以轻微的胰岛素抵抗现象为次但以胰岛素分泌不足为主。[3]

与2型糖尿病和胰岛素抵抗有关的其他潜在重要机制包括:脂肪细胞内脂质的分解有增加的情况、对肠促胰岛素(Incretin)的抵抗和缺乏、血液里的胰高血糖素水平过高、肾脏积蓄的盐份和水份出现上升,及中枢神经系统引致的代谢规律不正常。[6]然而,并不是所有出现胰岛素抗体的人士都会患上糖尿病,而是胰岛β细胞同时出现胰岛素分泌障碍的情况下才会发病。[3]

诊断

| 条件 | 餐后两小时血糖 | 空腹血糖 | HbA1c |

|---|---|---|---|

| mmol/l(mg/dl) | mmol/l(mg/dl) | % | |

| 正常 | <7.8(<140) | <6.1(<100) | <5.7 |

| 空腹血糖障碍 | <7.8(<140) | ≥6.1(≥100)& <7.0(<126) | 5.7–6.4 |

| 糖耐量受损 | ≥7.8(≥140) | <7.0(<126) | 5.7–6.4 |

| 糖尿病 | ≥11.1(≥200) | ≥7.0(≥126) | ≥6.5 |

世界卫生组织定义糖尿病(1型和2型)为有症状之单次血糖值上升,或两次血糖值上升涉及[26]

- 空腹血糖≥7.0毫摩尔/升(126毫克/分升)

- 或

- 作出糖耐力测试,口服两小时之后,血糖≥11.1毫摩尔/升(200毫克/分升)。

与典型症状有关的随机血糖高于11.1毫摩尔/升(200毫克/分升)[5]或糖化血红蛋白(HbA1c)高于6.5%是也一种诊断糖尿病的方法。[6]2009年,一个由美国糖尿病协会(American Diabetes Association,简称ADA)、国际糖尿病联合会(International Diabetes Federation,简称IDF)和欧洲糖尿病研究协会(European Association for the Study of Diabetes,简称EASD)代表的国际专家委员会(International Expert Committee)建议糖尿病诊断应该使用临界阈≥6.5% HbA1c。[27]美国糖尿病协会于2010年采用此建议。[28]只有病患出现典型症状和血糖>11.1 毫摩尔/升(>200 毫克/分升)才应该重复进行阳性检验。[27]

诊断糖尿病之临界阈是根据糖耐力测试、空腹血糖或HbA1c和并发症如视网膜病变(Retinopathy)结果之关系。[6]比起糖耐力测试,空腹或随机血糖因为比较方便,而显得更适用。[6]HbA1c的优点是不需禁食及结果较稳定,但是缺点是检验较血糖测量昂贵。[29]在美国,估计有20%患糖尿病的人并不知道自己患有糖尿病。[6]

2型糖尿病的特征是在胰岛素抵抗和相对胰岛素缺乏的情况下出现高血糖。[2]这与1型糖尿病大不相同,其中绝对胰岛素缺乏是由于胰脏胰岛细胞损坏及妊娠期糖尿病(即与怀孕有关的高血糖)的发病所导致。[3]1型和2型糖尿病通常可以根据实际状况来区分。[27]如果对诊断存在疑问,抗体试验可能有助于判定一型糖尿病,C-反应肽(C-peptide)水平则可能有助于判定2型糖尿病。[30]

筛查

由于没有证据证明大面积糖尿病筛查可改善最终结果,因此没有主要部门建议进行普查。[31]美国预防服务任务小组(United States Preventive Services Task Force)建议对没有症状且血压高于135/80毫米水银柱的成年人进行筛查。[32]对于血压较低的人,并没有充分证据支持或反对进行筛查。[32]世界卫生组织建议只对高危人群进行检验。[31]在美国的高危人群包括:45岁以上人士;有一级亲属患有糖尿病的人士;包括西班牙裔美国人、非裔美国人和美洲土著等族群;妊娠期糖尿病、多囊卵巢综合症、体重过高和与代谢综合征有关情况的病史。[5]

预防

通过适当营养和经常运动,可以延缓或防止2型糖尿病的发病。[33][34]强化生活方式可以将风险减半。[7]不管某人的最初多重或后来的体重是否减轻,运动皆会有益处。[35]不过,支持单靠饮食改变便会有益处的证据有限,[36]一些证据支持有富含绿叶蔬菜的饮食,[37]也有一些证据支持限制含糖饮料的摄入。[12]对于糖耐量受损(Impaired glucose tolerance)的人士,单单改变饮食习惯及运动,或一并摄取二甲双胍(Metformin)或阿卡波糖(Acarbose),可以将糖尿病的风险减低。[7][38]改变生活方式比二甲双胍还有效。[7]

管理

2型糖尿病管理着重于生活方式干预、减低其他心血管风险因素和维持血糖水平界于正常范围。[7]2008年,英国国民医疗服务制度(National Health Service)建议2型糖尿病初诊人士进行血糖的自我监测,[39]但是对于没有使用多剂量胰岛素的人士,自我监测的益处是令人置疑的。[7][40]其他心血管风险因素如高血压、高胆固醇和微量白蛋白尿(Microalbuminuria)的管理会改善预期寿命。[7]相对于标准血压管理(低于140-160/85-100毫米水银柱),强化血压管理(低于130/80毫米水银柱)使中风风险轻微减低,但是对总体的死亡风险并没有影响。[41]

相对于标准血压降低(HbA1C7-7.9%),强化血压降低(HbA1C<6%)似乎并未改变死亡率。[42][43]治疗目标通常是HbA1C低于7%或空腹血糖低于6.7毫摩尔/升(120毫克/分升);但是对低血糖症和预期寿命的特别风险加以考虑,这些目标在专业临床会诊后可以改变。[5]建议所有患有2型糖尿病的人士经常进行眼科检查。[3]

生活方式

适当的饮食和运动是糖尿病治疗的基础,[5]更大的运动量可产生更好的结果。[44]有氧运动可使HbA1c下降并改善胰岛素敏感性。[44]耐力训练(Resistance training)也有作用,而这两种类型的运动的组合可能是最有效的。[44]促进减肥的糖尿病饮食是很重要的。[45]尽管实现这一目标的最佳饮食类型尚有争议,[45]但已发现低血糖饮食(Low-glycemic diet)可改善血糖控制。[46]文化上适当的教育可以帮助2型糖尿病人控制血糖水平,至少达6个月以上。[47]如果生活方式的变化未在六个月内改善轻度糖尿病的血糖,则应考虑药物治疗。[5]

药物

目前有几类抗糖尿病药。由于有证据表明二甲双胍(Metformin)可降低死亡率,因此通常将其作为第一线治疗药物。[7]如二甲双胍不足以控制病情,则可使用另一个类的辅助口服制剂。[48]其他类别的药物包括:磺酰脲类、非磺脲类分泌抑制剂、α-葡萄糖苷酶抑制剂(alpha-glucosidase inhibitor)、噻唑烷二酮类药物(Thiazolidinedione)、胰高血糖素样肽-1类似物、二肽基肽酶-4抑制剂(Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor)以及钠-葡萄糖协同转运蛋白2抑制剂(SGLT2抑制剂)。[7][49]二甲双胍不应该用于患有严重肾脏或肝脏功能异常的患者。[5]胰岛素注射可用于配合口服药物治疗,或单独使用。[7]

大多数人最初都无需注射胰岛素。[3]当使用时,通常在夜间采用一种长效制剂,同时继续口服药物。[5][7]剂量随后增加至起效(血糖水平达到很好的控制)。[7]当夜间胰岛素不足,每日两次胰岛素可达到更好的控制。[5]长效胰岛素,甘精胰岛素(glargine)和地特胰岛素同样安全、有效,[50]并不比中性NPH胰岛素更好,但因为花费明显更高,所以它们不具备成本效益。[51][注 1]对于怀孕的患者,胰岛素是通常的治疗选择。[5]

外科手术

对于超重的患者,减肥手术是治疗糖尿病的有效措施。[52]许多人手术后,能够维持正常的血糖水平并服用很少或根本不服用药物,[53]且降低了长期死亡率。[54]不过仍存在低于1%的短期手术死亡风险。[55]但适用于手术的身高體重指數临界值尚不清楚。[54]然而,对于那些无法控制体重和血糖的人,推荐使用这个方法。[56]

流行病学

| 无数据 ≤ 7.5 7.5–15 15–22.5 22.5–30 30–37.5 37.5–45 | 45–52.5 52.5–60 60–67.5 67.5–75 75–82.5 ≥ 82.5 |

2010年估計全球2型糖尿病患者約有2亿8500万人,占糖尿病患者的90%,[6]約相当于世界成人人口的6%。[57]糖尿病是发达国家和发展中国家常见的疾病。[6]在经济欠发达地区仍然相當罕见。[3]

女性[6][58]以及南亚裔、太平洋岛民(Pacific Islander)、拉美裔(Latino)和美洲原住民等族裔群体似乎有更高的患病风险。[5]这可能是由于這些群体对西方的生活方式更为敏感。[59]传统上2型糖尿病歸類為成人疾病,然而随着儿童肥胖率的增加,越来越多的儿童也被诊断罹患2型糖尿病。[6]美国青少年被诊断为2型糖尿病的频率与1型糖尿病同样频繁。[3]

糖尿病患者在1985年的数量估计在3000万,在1995年增至1亿3500万,2005年增加至2亿1700万。[60]增加的原因主要是全球人口老龄化,运动减少和肥胖率增加。[60]至2000年為止,糖尿病患者数最多的五个国家是印度(3170万)、中国(2080万)、美国(1770万)、印度尼西亚(840万)和日本(680万)。[61]糖尿病被世界卫生组织确认为一种全球性流行病。[62]

根据最新的调查数据统计,中国糖尿病前期患病率已经到达惊人的50.1%,相当于一半中国人具有潜在发展成为糖尿病的风险引证错误:<ref>标签中未填内容的引用必须填写name属性。

历史

糖尿病是首先有记载的疾病之一,[63]公元前约1500年的埃及手稿将其称为“尿液过度排空”。[64]首个有记载的病例被认为是1型糖尿病。[64]印度的医生在同期确定了该病,并将其归类为“蜜糖尿”(madhumeha),因为尿液会引来蚂蚁。[64]而“diabetes”(意为“to pass through”)一词由希腊人孟菲斯之阿波罗尼奥斯(Apollonius of Memphis)在公元前230年首次使用。[64]在罗马帝国时期,该病属于罕见病,盖伦指出,在他的职业生涯中只见过两例。[64]

公元400-500年,印度医生Sushruta和Charaka首次将1型和2型糖尿病区分开来,认为1型与青年有关,而2型与超重有关。[64]“mellitus”一词由英国人约翰·罗尔(John Rolle)于1700年代末期首次使用,用于与频繁排尿的尿崩症相区分。[64]直到20世纪早期,加拿大人弗雷德里克·班廷和查尔斯·贝斯特在1921年和1922年发现胰岛素之前,[64]该病一直没有有效的治疗。 随后又在1940年代开发出长效NPH胰岛素。[64]

参考文献

- ^ Diabetes Blue Circle Symbol. International Diabetes Federation. 17 March 2006.

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Abbas, Abul K.; Cotran, Ramzi S. ; Robbins, Stanley L. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease 7th. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders. 2005: 1194–1195. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

- ^ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 Shoback, edited by David G. Gardner, Dolores. Greenspan's basic & clinical endocrinology 9th. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2011: Chapter 17. ISBN 0-07-162243-8.

- ^ Fasanmade, OA; Odeniyi, IA, Ogbera, AO. Diabetic ketoacidosis: diagnosis and management. African journal of medicine and medical sciences. 2008 Jun, 37 (2): 99–105. PMID 18939392.

- ^ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 Vijan, S. Type 2 diabetes. Annals of internal medicine. 2010-03-02, 152 (5): ITC31–15; quiz ITC316. PMID 20194231. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-01003.

- ^ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Williams textbook of endocrinology. 12th. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders. : 1371–1435. ISBN 978-1-4377-0324-5.

- ^ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 Ripsin CM, Kang H, Urban RJ. Management of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am Fam Physician. January 2009, 79 (1): 29–36. PMID 19145963.

- ^ Pasquier, F. Diabetes and cognitive impairment: how to evaluate the cognitive status?. Diabetes & metabolism. 2010 Oct,. 36 Suppl 3: S100–5. PMID 21211730. doi:10.1016/S1262-3636(10)70475-4.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Risérus U, Willett WC, Hu FB. Dietary fats and prevention of type 2 diabetes. Progress in Lipid Research. January 2009, 48 (1): 44–51. PMC 2654180

. PMID 19032965. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2008.10.002.

. PMID 19032965. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2008.10.002.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Touma, C; Pannain, S. Does lack of sleep cause diabetes?. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2011 Aug, 78 (8): 549–58. PMID 21807927. doi:10.3949/ccjm.78a.10165.

- ^ Christian, P; Stewart, CP. Maternal micronutrient deficiency, fetal development, and the risk of chronic disease. The Journal of nutrition. 2010 Mar, 140 (3): 437–45. PMID 20071652. doi:10.3945/jn.109.116327.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Malik, VS; Popkin, BM, Bray, GA, Després, JP, Hu, FB. Sugar Sweetened Beverages, Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease risk. Circulation. 2010-03-23, 121 (11): 1356–64. PMC 2862465

. PMID 20308626. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185.

. PMID 20308626. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185.

- ^ Malik, VS; Popkin, BM, Bray, GA, Després, JP, Willett, WC, Hu, FB. Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010 Nov, 33 (11): 2477–83. PMC 2963518

. PMID 20693348. doi:10.2337/dc10-1079.

. PMID 20693348. doi:10.2337/dc10-1079.

- ^ Hu, EA; Pan, A, Malik, V, Sun, Q. White rice consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis and systematic review. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2012-03-15, 344: e1454. PMC 3307808

. PMID 22422870. doi:10.1136/bmj.e1454.

. PMID 22422870. doi:10.1136/bmj.e1454.

- ^ Lee, I-Min; Shiroma, Eric J; Lobelo, Felipe; Puska, Pekka; Blair, Steven N; Katzmarzyk, Peter T. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet. 1 July 2012. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Herder, C; Roden, M. Genetics of type 2 diabetes: pathophysiologic and clinical relevance. European journal of clinical investigation. 2011 Jun, 41 (6): 679–92. PMID 21198561. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02454.x.

- ^ Monogenic Forms of Diabetes: Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus and Maturity-onset Diabetes of the Young. National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse (NDIC) (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH). 2007年3月 [2008-08-04].

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Bethel, edited by Mark N. Feinglos, M. Angelyn. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: an evidence-based approach to practical management. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. 2008: 462. ISBN 978-1-58829-794-5.

- ^ Izzedine, H; Launay-Vacher, V, Deybach, C, Bourry, E, Barrou, B, Deray, G. Drug-induced diabetes mellitus. Expert opinion on drug safety. 2005 Nov, 4 (6): 1097–109. PMID 16255667. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.6.1097.

- ^ Sampson, UK; Linton, MF, Fazio, S. Are statins diabetogenic?. Current opinion in cardiology. 2011 Jul, 26 (4): 342–7. PMC 3341610

. PMID 21499090. doi:10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283470359.

. PMID 21499090. doi:10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283470359.

- ^ Saad F, Gooren L. The role of testosterone in the metabolic syndrome: a review. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. March 2009, 114 (1–2): 40–3. PMID 19444934. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.022.

- ^ Farrell JB, Deshmukh A, Baghaie AA. Low testosterone and the association with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2008, 34 (5): 799–806. PMID 18832284. doi:10.1177/0145721708323100.

- ^ Diabetes mellitus a guide to patient care.. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007: 15. ISBN 978-1-58255-732-8.

- ^ Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: report of a WHO/IDF consultation (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2006: 21. ISBN 978-92-4-159493-6.

- ^ Vijan, Sandeep. Type 2 Diabetes. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010-03-02, 152 (5): ITC3–1. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 20194231. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-01003 (英语).

- ^ World Health Organization. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: Report of a WHO Consultation. Part 1. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. [29 May 2007].

- ^ 27.0 27.1 27.2 International Expert, Committee. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009 Jul, 32 (7): 1327–34. PMC 2699715

. PMID 19502545. doi:10.2337/dc09-9033.

. PMID 19502545. doi:10.2337/dc09-9033.

- ^ Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care (American Diabetes Association). January 2010,. 33 Suppl 1 (Supplement_1): S62–9. PMC 2797383

. PMID 20042775. doi:10.2337/dc10-S062.

. PMID 20042775. doi:10.2337/dc10-S062.

- ^ American Diabetes, Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. January 2012,. 35 Suppl 1: S64–71. PMID 22187472. doi:10.2337/dc12-s064.

- ^ Diabetes mellitus a guide to patient care.. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007: 201. ISBN 978-1-58255-732-8.

- ^ 31.0 31.1 Valdez R. Detecting Undiagnosed Type 2 Diabetes: Family History as a Risk Factor and Screening Tool. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009, 3 (4): 722–6. PMC 2769984

. PMID 20144319.

. PMID 20144319.

- ^ 32.0 32.1 Screening: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Adults. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2008 [2014-03-16].

- ^ Raina Elley C, Kenealy T. Lifestyle interventions reduced the long-term risk of diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance. Evid Based Med. December 2008, 13 (6): 173. PMID 19043031. doi:10.1136/ebm.13.6.173.

- ^ Orozco LJ, Buchleitner AM, Gimenez-Perez G, Roqué I Figuls M, Richter B, Mauricio D. Mauricio, Didac , 编. Exercise or exercise and diet for preventing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, (3): CD003054. PMID 18646086. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003054.pub3.

- ^ O'Gorman, DJ; Krook, A. Exercise and the treatment of diabetes and obesity. The Medical clinics of North America. 2011 Sep, 95 (5): 953–69. PMID 21855702. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2011.06.007.

- ^ Nield L, Summerbell CD, Hooper L, Whittaker V, Moore H. Nield, Lucie , 编. Dietary advice for the prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, (3): CD005102. PMID 18646120. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005102.pub2.

- ^ Carter, P; Gray, LJ, Troughton, J, Khunti, K, Davies, MJ. Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2010-08-18, 341: c4229. PMC 2924474

. PMID 20724400. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4229.

. PMID 20724400. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4229.

- ^ Santaguida PL, Balion C, Hunt D; et al. Diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose (PDF). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). August 2005, (128): 1–11. PMID 16194123.

- ^ Clinical Guideline:The management of type 2 diabetes (update).

- ^ Farmer, AJ; Perera, R, Ward, A, Heneghan, C, Oke, J, Barnett, AH, Davidson, MB, Guerci, B, Coates, V, Schwedes, U, O'Malley, S. Meta-analysis of individual patient data in randomised trials of self monitoring of blood glucose in people with non-insulin treated type 2 diabetes.. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2012 Feb 27, 344: e486. PMID 22371867.

- ^ McBrien, K; Rabi, DM; Campbell, N; Barnieh, L; Clement, F; Hemmelgarn, BR; Tonelli, M; Leiter, LA; Klarenbach, SW; Manns, BJ. Intensive and Standard Blood Pressure Targets in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.. Archives of internal medicine. 2012 Aug 6: 1–8. PMID 22868819.

- ^ Boussageon, R; Bejan-Angoulvant, T, Saadatian-Elahi, M, Lafont, S, Bergeonneau, C, Kassaï, B, Erpeldinger, S, Wright, JM, Gueyffier, F, Cornu, C. Effect of intensive glucose lowering treatment on all cause mortality, cardiovascular death, and microvascular events in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2011-07-26, 343: d4169. PMC 3144314

. PMID 21791495. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4169.

. PMID 21791495. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4169.

- ^ Webster, MW. Clinical practice and implications of recent diabetes trials. Current opinion in cardiology. 2011 Jul, 26 (4): 288–93. PMID 21577100. doi:10.1097/HCO.0b013e328347b139.

- ^ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Zanuso S, Jimenez A, Pugliese G, Corigliano G, Balducci S. Exercise for the management of type 2 diabetes: a review of the evidence. Acta Diabetol. March 2010, 47 (1): 15–22. PMID 19495557. doi:10.1007/s00592-009-0126-3.

- ^ 45.0 45.1 Davis N, Forbes B, Wylie-Rosett J. Nutritional strategies in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mt. Sinai J. Med. June 2009, 76 (3): 257–68. PMID 19421969. doi:10.1002/msj.20118.

- ^ Thomas D, Elliott EJ. Thomas, Diana , 编. Low glycaemic index, or low glycaemic load, diets for diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, (1): CD006296. PMID 19160276. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006296.pub2.

- ^ Hawthorne, K.; Robles, Y.; Cannings-John, R.; Edwards, A. G. K.; Robles, Yolanda. Robles, Yolanda , 编. Culturally appropriate health education for Type 2 diabetes mellitus in ethnic minority groups. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, (3): CD006424. PMID 18646153. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006424.pub2. CD006424.

- ^ Qaseem, A; Humphrey, LL, Sweet, DE, Starkey, M, Shekelle, P, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of, Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2012-02-07, 156 (3): 218–31. PMID 22312141. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00011.

- ^ American Diabetes, Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2012. Diabetes Care. January 2012,. 35 Suppl 1: S11–63. PMID 22187469. doi:10.2337/dc12-s011.

- ^ Swinnen, SG.; Simon, AC.; Holleman, F.; Hoekstra, JB.; Devries, JH. Simon, Airin CR , 编. Insulin detemir versus insulin glargine for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, (7): CD006383. PMID 21735405. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006383.pub2.

- ^ Waugh, N; Cummins, E, Royle, P, Clar, C, Marien, M, Richter, B, Philip, S. Newer agents for blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2010 Jul, 14 (36): 1–248. PMID 20646668. doi:10.3310/hta14360.

- ^ Picot, J; Jones, J, Colquitt, JL, Gospodarevskaya, E, Loveman, E, Baxter, L, Clegg, AJ. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2009 Sep, 13 (41): 1–190, 215–357, iii–iv. PMID 19726018. doi:10.3310/hta13410.

- ^ Frachetti, KJ; Goldfine, AB. Bariatric surgery for diabetes management. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity. 2009 Apr, 16 (2): 119–24. PMID 19276974. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e32832912e7.

- ^ 54.0 54.1 Schulman, AP; del Genio, F, Sinha, N, Rubino, F. "Metabolic" surgery for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2009 Sep-Oct, 15 (6): 624–31. PMID 19625245. doi:10.4158/EP09170.RAR.

- ^ Colucci, RA. Bariatric surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes: a viable option. Postgraduate Medicine. 2011 Jan, 123 (1): 24–33. PMID 21293081. doi:10.3810/pgm.2011.01.2242.

- ^ Dixon, JB; le Roux, CW; Rubino, F; Zimmet, P. Bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes.. Lancet. 2012 Jun 16, 379 (9833): 2300–11. PMID 22683132.

- ^ Meetoo, D; McGovern, P, Safadi, R. An epidemiological overview of diabetes across the world. British journal of nursing (Mark Allen Publishing). 2007 Sep 13-27, 16 (16): 1002–7. PMID 18026039.

- ^ Abate N, Chandalia M. Ethnicity and type 2 diabetes: focus on Asian Indians. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2001, 15 (6): 320–7. PMID 11711326. doi:10.1016/S1056-8727(01)00161-1.

- ^ Carulli, L; Rondinella, S, Lombardini, S, Canedi, I, Loria, P, Carulli, N. Review article: diabetes, genetics and ethnicity. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2005 Nov,. 22 Suppl 2: 16–9. PMID 16225465. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02588.x.

- ^ 60.0 60.1 Smyth, S; Heron, A. Diabetes and obesity: the twin epidemics. Nature Medicine. 2006 Jan, 12 (1): 75–80. PMID 16397575. doi:10.1038/nm0106-75.

- ^ Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. May 2004, 27 (5): 1047–53. PMID 15111519. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047.

- ^ Diabetes Fact sheet N°312. World Health Organization. Aug 2011 [9 January 2012].

- ^ Ripoll, Brian C. Leutholtz, Ignacio. Exercise and disease management 2nd. Boca Raton: CRC Press. 2011-04-25: 25. ISBN 978-1-4398-2759-8.

- ^ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 64.4 64.5 64.6 64.7 64.8 editor, Leonid Poretsky,. Principles of diabetes mellitus 2nd. New York: Springer. 2009: 3. ISBN 978-0-387-09840-1.

- 附注

- ^ 截至2010年不具备成本效益

外部链接

| 维基词典上的字词解释 | |

| 维基共享资源上的多媒体资源 | |

| 维基新闻上的新闻 | |

| 维基语录上的名言 | |

| 维基文库上的原始文献 | |

| 维基教科书上的教科书和手册 | |

| 维基学院上的學習资源 | |

- 开放式目录计划中和2型糖尿病相关的内容

- 国家糖尿病信息中心

- 美国疾病控制中心(内分泌病理)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||